|

||||||

| Read: | View the Aerial Photo: | Watch the videos: | ||||

The Facts about our |

Aerial Photo w/ Survey |

Video #1 - Introduction |

Video #2 - Successors & Assigns |

Video #3 - Triplex Common Areas |

||

| Click the links below for more information: | |

| Where Will They Park? | |

| 20+ Reasons Why There Is No Easement | |

| Bogus Attorney Fees | |

| New Castle County Department of Land Use | |

| Unclean Hands | |

| Delaware Chancery Court & New Castle County Sanctioned Land Grab | |

| Related Cases | |

| Deerhurst | |

| Historic Photos - The way it was... | |

| Illegal Pressure Washing | |

| Blackball Properties LLC | |

| Wrong Way on 202 | |

| Tell Us Your Story | |

| What They Are Saying | |

| Get Involved | |

| |

|

Share this on Facebook by pressing "Like": |

|

We are the property and business owners of 1703 and 1709 Concord Pike in Wilmington, Delaware. We oppose the change of use of 1707 Concord Pike from general office to light auto service (auto detailing). It has been 761 weeks and 6 days since we first complained to New Castle County about this property. |

|

For all of you who own commercial properties in New Castle County or represent those who do, it seems that changing the use of a nonconforming property to a more intensive use does not require you come up to current code. If you have been spending tens of thousands of dollars to reduce your square footage, engineer parking plans, and/or get variances from the Board of Adjustment, then you have been duped by the Land Use Department. And for those of you like us who have shared parking, be prepared to be overrun when one of your neighbors changes to a more intensive use. The County will lie to you and then look the other way. In their eyes, "shared parking" means "unlimited parking" and UDC Section 40.22.611 Subsection K does not apply. |

|

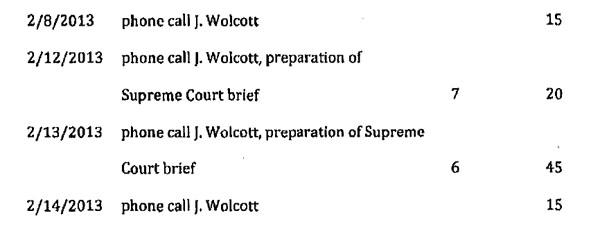

Bogus Attorney Fees - There was no "bad faith" and the claimed amount is unreasonableOur neighbors claim to have spent $184,320.47 in legal fees which includes additional fees for their out-of-state attorney & high school classmate to write their Delaware Supreme Court answering brief when they claimed to be representing themselves (pro se) in the Appeal.

From our Delaware Supreme Court Opening Brief: Finally, the Order's assertion that the County warned the Blacks "that their claimed rights were contested" is incorrect. Instead, the County advised the Staffieris that they might possess rights to use the parking and driveway areas on the Triplex Properties. And the County advised the Blacks that installing the fence was permissible. Only the Staffieris contested the Blacks' legal position, first doing so 4+ months after the fence and roll stops were installed. If opposition to an opposing party's position alone is sufficient to award attorneys fees, then the Bad Faith Exception to the American Rule will be transformed into a mere "Prevailing Party" rule that completely eviscerates the American Rule in Delaware jurisprudence. Accordingly, the Order's award of fees sets a dangerous precedent. This Court has previously held that "[g]enerally, the Bad Faith Exception

for the American Rule for attorneys' fees 'does not apply to the conduct that

gives rise to the substantive claim itself."' Versata Enteprises, Inc., supra. In This Court has previously held that "courts have found bad faith where parties have unnecessarily prolonged or delayed litigation, falsified records, or knowingly asserted frivolous claims." Johnston v. Arbitrium (Cayman Islands) Handels AG, 720 A.2d 542, 546 (Del. 1998). The Blacks' legal position was not frivolous. At most, the Blacks relied upon a losing, albeit plausible, legal interpretation of Deed language. That does not meet the high Bad Faith standard. In the end, the trial court's award of fees, if allowed to stand, would mean that the Bad Faith Exception is now nothing more than a "Prevailing Party" rule: the Bad Faith Exception would swallow the American Rule whole. Thus, the Trial Court erred. A good example of the egregious type of conduct necessary to establish

an entitlement to an award of fees under the Bad Faith Exception is presented

by Judge v. City of Rehoboth Beach, 1994 WL 198700, *2-3, Chandler, V.C. In direct contradistinction to Judge: I) the Staffieris' right to use the driveway and parking areas on the Triplex Properties was not previously adjudicated; 2) the Blacks' lawyers agreed with their position; and 3) the Blacks' possessed a valid, good faith Deed interpretation argument supporting their position. Under these circumstances, the record establishes that the award of fees to the Staffieris was arbitrary and capricious. The type of bad faith award granted in Judge is referred to in Court of Chancery jurisprudence as a "subset" of the Bad Faith Exception, where a defendant's conduct forced the plaintiff to file suit to "secure a clearly defined and established right." McGowan v. Empress Entertainment, Inc., 791 A.2d I, 4 (Del. Ch. 2000). The fact that the Order had to construe the Deed language and rely upon extrinsic evidence proves that the rights were not clearly established in the Deed. The Order was the first time that rights were clearly established. Consequently, the award of attorneys fees was in error. Unreasonable Fee AmountsThe Trial Court awarded attorneys fees and litigation expenses in the

amount of $176,670.47 slightly less than the total amount of $184,320.47

requested. The award constituted 95% of fees and 100% of expenses. Cf. Id. and The Plaintiffs only prevailed on one (1) of eight (8) claims asserted: Express Easement. The Plaintiffs improvidently pursued numerous alternative and additional claims, most of which were unnecessary and had no legitimate prospect of success on the merits. As a result, considerable time was chewed up in the litigation chasing farfetched, "shotgun approach" causes. On these grounds alone, the fees awarded should have been no more than one-half (1/2) of the final "reasonable" amount. The Court should deny a substantial portion of the Staffieris' fee demand on the grounds that the amount of time expended is excessive. The assertion by Ms. Cherry that she spent 60+ hours preparing a brief and 60+ hours preparing for trial is outlandish and excessive. And her fees incurred performing non-litigation work are simply not awardable. The fact that Ms. Cherry's bills do not provide the degree of specificity customary in Delaware practice and necessary for the Court to evaluate the legitimacy of her time is additional cause to significantly reduce the hours awarded. A substantial reduction in her bill is warranted due to the paucity of proof that her hours were reasonable. Block billing with amorphous task descriptions are insufficient. Additionally, numerous wasteful efforts evidence Ms. Cherry's lack of experience and ability in Delaware law generally and real property law specifically. Futile Preliminary Injunction and Summary Judgment practice wasted tens of thousands of dollars in time. Associating with a supposed "local" counsel who could not legally litigate the action wasted more money. Further, fees charged by Mr. Wolcott to attend the trial should be denied in their entirety: a total of 14.8 hours or $3,700. Ms. Cherry tried the entire case and was admitted pro hac vice, thereby rendering Mr. Wolcott's presence at the 2+ day trial unnecessary. Finally, Mr. Karagelian unnecessarily incurred fees on the ill-fated Preliminary Injunction request. Specifically, his bill reflects about 9.3 hours at $300 per hour, or $2,790, was wasted. The Court should also deny Ms. Cherry's claim for fees regarding her involvement in appeal matters. A-571. She was not admitted pro hac vice in the Supreme Court. And the Staffieris submitted their Answering Brief on appeal pro se. Ms. Cherry claimed appeal related time of 22.3 hours, which equates to unawardable fees of $6,690. Ms. Cherry's initial request was for $114,000 in fees and her

supplemental request was for $7,450, for a total of $121,450. Specific deductions for unawardable time in the form of a title

insurance claim, representation vis a vis New Castle County, and the appeal

justifies a reduction in her billings of$16,040, to $105,410. That amount should be reduced by 50% based on the

various wasteful efforts, the excessive and duplicative nature of her bills, and

her overly general block billing. This results in maximum "reasonable" fees of

$52,705. A further 50% reduction based upon the fact that the Staffieris

prevailed, at best, on only one-half of their claims in the action would result in a

maximum fee award in the amount of $26,352.50 for Ms. Cherry's work. |